Ehsa Murray

As a queer, Asian American artist, my artworks focus on identity and community. I communicate these themes through stories from my own life, which I capture through my artwork. The Micro and the Macro of Anti-Asian Racism is meant to bring awareness to both the broader and more specific patterns of Anti-Asian racism. It is meant to connect Asian Americans to each other, and to inspire conversation about the Asian American experience not just within the community, but outside of it as well.

I am a fifth generation Japanese American, though I am only half on my mother’s side. I am a member of the Arizona Buddhist Temple, where I grew up in a small, Japanese American community. Many of the older members of my temple, such as my Ojiichan (grandfather), grew up in Japan during World War II, before moving to America in his adulthood. During World War II, many of them, such as my Obaachan (grandmother), were interned at Gila River Relocation Center. The long-term effects of this period of history can still be seen in my family, and in me. My Japanese heritage is woven into every part of who I am. My Capstone is a deeply personal project, and could not have been created without the encouragement and aid of my community.

For my project, I chose a combination of relief print and watercolor. I chose relief so that I could make multiple copies of my illustrated works. I chose watercolor to evoke a dreamlike quality in the artwork. My artwork is characterized by its smooth blending and its vibrant colors.

I find inspiration through comic books and illustrations. My project pays homage to the comic Maus by Art Spiegelman. I have used Spiegelman’s artwork as a reference throughout the creation of this piece, studying both his ability to portray the events of the Holocaust in a strong, visually cohesive manner, as well as his exploration of generational trauma and its bearings on the storyteller. I have also been referencing books and poetry created by Asian American writers.

How Much Do You Know About Asian Americans

This artwork was inspired by a memory from my junior year of my undergraduate studies. I took an “Asian Americans in Film” class as part of my minor, taught by Dr. Nitika Sharma. On the first day, Dr. Sharma asked the class to raise our hands if we either knew anyone who was Asian American, or if we knew anything about Asian culture. To my shock, most of the people who raised their hands were other Asian Americans, even though there were only about 7 of us in the roughly 30-person class. One non-Asian student who had raised her hand said that she had friends who are Asian American, but they never talked about their culture or their experiences with her. I found this statement surprising, because all the Asian Americans I know frequently talk about their culture and how it affects their experiences.

This moment became the inspiration for The Micro and the Macro of Anti-Asian Racism.

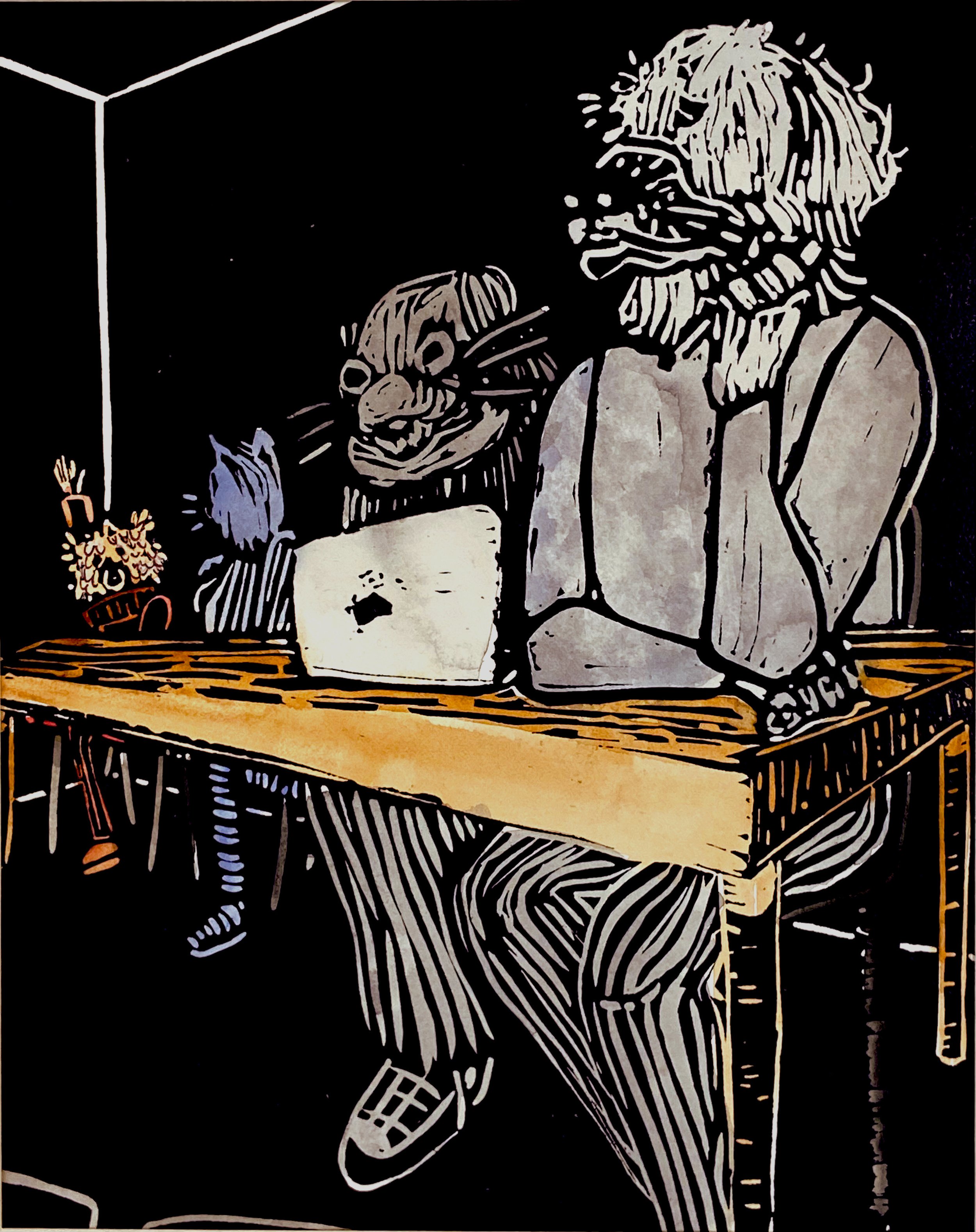

宠物 (Pet)

The story for this artwork came from a close friend of mine. In her interview, she said she once talked to a non-Asian classmate who seemed romantically interested in her. The more she talked to him, however, the more she realized he was only interested in her because she is Japanese. When he began asking if she liked anime and K-pop immediately after being introduced (something she had not seen him ask any of their non-Asian classmates), she quickly ended the conversation.

炊飯器頭 (Rice Cooker Head)

This artwork is based on a story from a childhood friend. He told me that once, when he was 13, there was a boy on his baseball team who was genuinely shocked to find out that Asian people did not have rice in their heads instead of brains. The title of this piece is “suihanki atama”, which translates to Rice Cooker Head.

Nemean Lion

This artwork is inspired by a phenomenon I observed among many of my friends and family with non-Western names. Whenever they need to give their name for something, for example at cafes and fast-food places, they tend to use Western names for convenience’s sake. “Chloe” or “Sam” is far easier for the average American to correctly pronounce; “Nanako” and “Sanjana”, not so much. My grandmother went by “Kaye” her whole life because “Kaoru” was often deemed too difficult to pronounce.

Monster in the Mirror

My friend and I were having a conversation about Asian representation in Western media. Many of the articles I had read on the topic talked about Eastern Asian representation, but none talked about Southeastern Asian representation. My friend, whose parents immigrated from India, brought up the common trope employed against Indian characters in the media: the “Funny Foreigner”. She cited Raj from “Big Bang Theory” and Timmy from “Rules of Engagement” as prominent examples.

Obaachan

“Obaachan” is a Japanese term of affection for grandmother. My obaachan was very affectionate towards me and my brothers; we spent nearly every day with her and my mom, and I can confidently say I remember those days at her house more than I remember anything else from my childhood. She loved us dearly, and we loved her.

My obaachan had a walk-in pantry that seemed to have every kind of food you could think of. I remember hiding in it during games of hide-and-seek. I remember sneaking in with my cousin and eating an entire tub of teriyaki nori before lunch. It felt like a wonderful place, full of all the foods my mom and dad didn’t have at home.

After her death, I found out that my Obaachan had been interned at Gila River Relocation Center when she was only 8 years old. She had hoarded food because of the food insecurity she had experienced during that time. Suddenly, that walk-in pantry took on new meaning, and I began to see the ways her trauma had woven its way into the lives of my mother and her siblings, and into my brothers and me. “Obaachan” is about generational trauma and the nearly invisible ways it has surrounded me. It is about a woman whom I remember with childish, unconditional love, who took on a different, stronger shape in my mind in the years following her death.